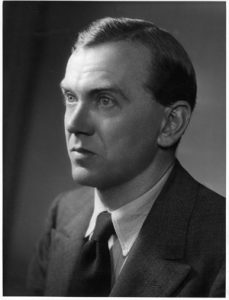

Henry Graham Greene, OM, CH was an English novelist, short story writer, playwright, screenplay writer, travel writer and critic whose works explore the ambivalent moral and political issues of the modern world. Greene combined serious literary acclaim with wide popularity.

Henry Graham Greene, OM, CH was an English novelist, short story writer, playwright, screenplay writer, travel writer and critic whose works explore the ambivalent moral and political issues of the modern world. Greene combined serious literary acclaim with wide popularity.

Although Greene objected strongly to being described as a “Catholic novelist” rather than as a “novelist who happened to be Catholic,” Catholic religious themes are at the root of much of his writing, especially the four major Catholic novels: Brighton Rock, The Heart of the Matter, The End of the Affair, and The Power and the Glory. Works such as The Quiet American, Our Man in Havana and The Human Factor also show an avid interest in the workings of international politics and espionage.

Books

Brighton Rock

A gang war is raging through the dark underworld of Brighton. Seventeen-year-old Pinkie, malign and ruthless, has killed a man. Believing he can escape retribution, he is unprepared for the courageous, life-embracing Ida Arnold. Greene’s gripping thriller, exposes a world of loneliness and fear, of life lived on the ‘dangerous edge of things’.

The Quiet American

“I never knew a man who had better motives for all the trouble he caused,” Graham Greene’s narrator Fowler remarks of Alden Pyle, the eponymous “Quiet American” of what is perhaps the most controversial novel of his career. Pyle is the brash young idealist sent out by Washington on a mysterious mission to Saigon, where the French Army struggles against the Vietminh guerrillas. As young Pyle’s well-intentioned policies blunder into bloodshed, Fowler, a seasoned and cynical British reporter, finds it impossible to stand safely aside as an observer. But Fowler’s motives for intervening are suspect, both to the police and himself, for Pyle has stolen Fowler’s beautiful Vietnamese mistress.

Originally published in 1956 and twice adapted to film, The Quiet American remains a terrifying and prescient portrait of innocence at large. This Graham Greene Centennial Edition includes a new introductory essay by Robert Stone.

The End of the Affair

“This is a record of hate far more than of love,” writes Maurice Bendrix in the opening passages of The End of the Affair, and it is a strange hate indeed that compels him to set down the retrospective account of his adulterous affair with Sarah Miles.

Now, a year after Sarah’s death, Bendrix seeks to exorcise the persistence of his passion by retracing its course from obsessive love to love-hate. At first, he believes he hates Sarah and her husband, Henry. Yet as he delves further into his emotional outlook, Bendrix’s hatred shifts to the God he feels has broken his life, but whose existence at last comes to recognize.

Champagne, if you are seeking the truth, is better than a lie detector.

But it is impossible to go through life without trust; that is to be imprisoned in the worst cell of all, oneself.

Hate is a lack of imagination.

Writing is a form of therapy; sometimes I wonder how all those who do not write, compose, or paint can manage to escape the madness, melancholia, the panic and fear which is inherent in a human situation.

The sense of unhappiness is so much easier to convey than that of happiness. In misery we seem aware of our own existence, even though it may be in the form of a monstrous egotism: this pain of mine is individual, this nerve that winces belongs to me and to no other. But happiness annihilates us: we lose our identity.

It’s a strange thing to discover and to believe that you are loved when you know that there is nothing in you for anybody but a parent or a God to love.