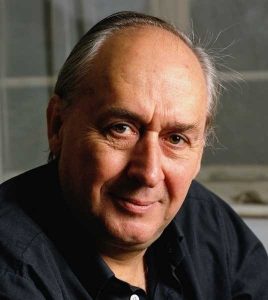

James Graham “J. G.” Ballard (15 November 1930 – 19 April 2009) was an English novelist, short story writer, and essayist. Ballard came to be associated with the New Wave of science fiction early in his career with apocalyptic (or post-apocalyptic) novels such as The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964), and The Crystal World (1966). In the late 1960s and early 1970s Ballard focused on an eclectic variety of short stories (or “condensed novels”) such as The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), which drew closer comparison with the work of postmodernist writers such as William S. Burroughs. In 1973 the highly controversial novel Crash was published, a story about symphorophilia and car crash fetishism; the protagonist becomes sexually aroused by staging and participating in real car crashes. The story was later adapted into a film of the same name by David Cronenberg.

James Graham “J. G.” Ballard (15 November 1930 – 19 April 2009) was an English novelist, short story writer, and essayist. Ballard came to be associated with the New Wave of science fiction early in his career with apocalyptic (or post-apocalyptic) novels such as The Drowned World (1962), The Burning World (1964), and The Crystal World (1966). In the late 1960s and early 1970s Ballard focused on an eclectic variety of short stories (or “condensed novels”) such as The Atrocity Exhibition (1970), which drew closer comparison with the work of postmodernist writers such as William S. Burroughs. In 1973 the highly controversial novel Crash was published, a story about symphorophilia and car crash fetishism; the protagonist becomes sexually aroused by staging and participating in real car crashes. The story was later adapted into a film of the same name by David Cronenberg.

While many of Ballard’s stories are thematically and narratively unusual, he is perhaps best known for his relatively conventional war novel, Empire of the Sun (1984), a semi-autobiographical account of a young boy’s experiences in Shanghai during the Second Sino-Japanese War as it came to be occupied by the Japanese Imperial Army. Described as “The best British novel about the Second World War” by The Guardian, the story was adapted into a 1987 film by Steven Spielberg.

The literary distinctiveness of Ballard’s work has given rise to the adjective “Ballardian”, defined by the Collins English Dictionary as “resembling or suggestive of the conditions described in J. G. Ballard’s novels and stories, especially dystopian modernity, bleak man-made landscapes and the psychological effects of technological, social or environmental developments.” The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry describes Ballard’s work as being occupied with “eros, thanatos, mass media and emergent technologies”.

Books

Crash

In this hallucinatory novel, the car provides the hellish tableau in which Vaughan, a “TV scientist” turned “nightmare angel of the highways,” experiments with erotic atrocities among auto crash victims, each more sinister than the last. James Ballard, his friend and fellow obsessive, tells the story of this twisted visionary as he careens rapidly toward his own demise in an intentionally orchestrated car crash with Elizabeth Taylor. A classic work of cutting edge fiction, Crash explores the disturbing potentialities of contemporary society’s increasing dependence on technology as intermediary in human relations.

High-Rise

When a class war erupts inside a luxurious apartment block, modern elevators become violent battlegrounds and cocktail parties degenerate into marauding attacks on “enemy” floors. In this visionary tale, human society slips into violent reverse as once-peaceful residents, driven by primal urges, re-create a world ruled by the laws of the jungle.

The Drowned World

First published in 1962, J.G. Ballard’s mesmerizing and ferociously prescient novel imagines a terrifying future in which solar radiation and global warming have melted the ice caps and Triassic-era jungles have overrun a submerged and tropical London. Set during the year 2145, the novel follows biologist Dr. Robert Kerans and his team of scientists as they confront a surreal cityscape populated by giant iguanas, albino alligators, and endless swarms of malarial insects. Nature has swallowed all but a few remnants of human civilization, and, slowly, Kerans and his companions are transformed–both physically and psychologically–by this prehistoric environment. Echoing Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness–complete with a mad white hunter and his hordes of native soldiers–this “powerful and beautifully clear” (Brian Aldiss) work becomes a thrilling adventure and a haunting examination of the effects of environmental collapse on the human mind.

Concrete Island

On a day in April, just after three o’clock in the afternoon, Robert Maitland’s car crashes over the concrete parapet of a high-speed highway onto the island below, where he is injured and, finally, trapped. What begins as an almost ludicrous predicament in Concrete Island soon turns into horror as Maitland – a wickedly modern Robinson Crusoe – realizes that, despite evidence of other inhabitants, this doomed terrain has become a mirror of his own mind. Seeking the dark outer rim of the everyday, Ballard weaves private catastrophe into an intensely specular allegory.

Cocaine Nights

When travel writer Charles Prentice arrives at Estrella de Mar, a resort town near Gibraltar populated primarily by British retirees, to find out why his brother Frank has been jailed, he’s shocked to find that Frank has confessed to a spectacular act of arson that left five people dead. Charles tries to find the real culprit by hanging around Estrella de Mar, which one resident describes as “like Chelsea or Greenwich Village in the 1960s. There are theatre and film clubs, a choral society, cordon blue classes…. Stand still for a moment and you find yourself roped into a revival of Waiting for Godot.” But the longer he stays, the more confused Charles is by the residents’ breezy lack of concern about the constant background of vandalism, rape, prostitution, and drug dealing.

Things become clearer as Charles makes the acquaintance of local tennis pro Bobby Crawford, who has some interesting hypotheses about how to maintain the quality of the inner life in the age of affluence. As another of the locals explains, “Leisure societies lie ahead of us, like those you see on this coast. People … will retire in their late thirties, with fifty years of idleness in front of them…. But how do you energize people, give them some sense of community?” Bobby’s succinct answer, provided to Charles in another context: “There’s nothing like a violent reflex now and then to tune up the nervous system.” Bobby convinces Charles to help him replicate his social experiment in an adjacent retirement community, slowly convincing him that crime and creativity really do go hand in hand. But who, if anybody, takes the responsibility?

I wanted to rub the human race in its own vomit, and force it to look in the mirror.

Fiction is a branch of neurology: the scenarios of nerve and blood vessels are the written mythologies of memory and desire.

Unhappy parents teach you a lesson that lasts a lifetime.

Civilised life, you know, is based on a huge number of illusions in which we all collaborate willingly. The trouble is we forget after a while that they are illusions and we are deeply shocked when reality is torn down around us.

I believe in the power of the imagination to remake the world, to release the truth within us, to hold back the night, to transcend death, to charm motorways, to ingratiate ourselves with birds, to enlist the confidences of madmen.

In a totally sane society, madness is the only freedom.

Sooner or later, everything turns into television.

After being bombarded endlessly by road-safety propaganda it was almost a relief to find myself in an actual accident.